It was the first day of spring, 2012. I was making a blossom jar.

Not because of any seasonal connotation. I make blossom jars all year round. In any case, seasons in this part of the world are better described as “the too much rain” or “not enough rain” season. The traditional four-in-one-year pattern seems to have fallen victim to climate change.

If I was to have made a diary entry on that day, which I didn’t because I don’t keep one, it most likely would not have mentioned blossom jars. More likely the entry would have featured a name, that of Dick Aitken, connoisseur and collector, commentator and ceramics enthusiast, especially wood fired.

It was early afternoon when Dick laboured up the steep, scrubby hill to my studio. He was out of breath and consequently, words, which is not his natural state. In the interim, his astute eyes scrutinised work lying around the room in various stages of completion.

Finally, they rested on the work in progress, a porcelain blossom jar.

The blossom jars I make are often described as vases and I think even that term is somewhat a stretch. In more recent times, (this, in the ceramic continuum, could be a lazy three or four decades or more), nondescript descriptions abound. Easily the most ubiquitous, and possibly vacuous, is “vessel”.

I eschew the term “vessel”, just like another: “ceramicist”. I agree with the potter Col Levy, who commented the word “ceramicist” sounded like some type of skin disorder.

The blossom jar I was making is best described as a spherical vase with a small opening, usually without a neck. I was once told that these were made to hold one or three sprigs of cherry blossom only, and the intrinsic “Japanese-ness” of this appealed instantly and indelibly.

It was Dick who commented that “blossom jar” was also a term used by Peter Rushforth among others, and we both envisaged some Jun and Tenmoku glazed pieces of the grand old master, with their hallmark rich opalescence and deep optical blues.

Peter fired in a double chamber wood kiln and the accidental surface variations featured breaks and trickles which conjured timeless images of clouds and valley-entrapped mist.

Later we spoke about Korean Moon Jars. This is ceramic lexicon at its most lyrical. They too were often made from porcelain, mostly in the later part of the Choson Dynasty, 1392-1910.

Korean scholar, Yi Kyu-gyong, wrote that “the greatest merit of white porcelain lies in it absolute purity”, and it takes no leap of imagination to perceive how this aesthetic aligned with austere Confucian taste.

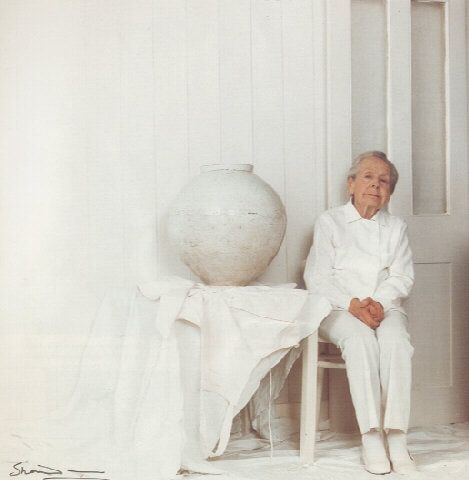

Historically, one of the more famous Moon Jars was the one owned by the redoubtable Lucie Rie. It was a gift from another 20th century icon, Bernard Leach, and it was photographed by a third, Lord Snowdon. Rie can be seen seated beside the pot, herself dressed in white.

The photo is visually stunning. It carries particular emotion. The huge jar placed on a nearby table seems to emerge out of white light, like time itself. It almost dwarfs Lucie Rie who is seated in front of a panelled white door.

The arrangement could be interpreted as a contemplation of portals, to disappear into or through, presumably to the past or a past narrative. Yet there is an inescapable sense of the present in this photograph. The elderly artist herself holds a queen-like posture, determinedly, and her positioning denies access to the other side of that door, and whatever exists beyond.

……. …….. …….

On the first day of spring, 2012, only a few white clouds sailed across a typically Queensland sky.

Sunsets, seen from the studio veranda, disappear behind a verdant green ridge. But for a good two hours before, sunlight slants through a tallowwood forest, across a lake and into the studio where Dick had taken a seat.

He had arrived with a project in mind - to interview me in consideration of an article for an industry journal.

He had no particular structure in mind, only a number of questions to shape something with.

Soon after the conversation began, I started to ask the questions. I like asking about people’s lives, many do, and way back when I was a kid, I was a journalist.

The role reversal fazed neither of us that afternoon.

There was too much in common - our love of wood firing being the foundation, our opinionated perspectives convenient conversational building blocks, and mutual respect the mortar.

I proposed we co-author an article, about wood fired ceramics that focussed less on methodologies, more its character.

Our conversation was circuitous. Conversations can resemble the shape and nature of rivers. In their infancy, they are more inclined to take the shortest path between two points, as if emerging from steeper country.

Then as they mature, as other tributaries feed the base water flow and they develop, they relax, slow and begin to loop, wind back on themselves.

As we spoke, we wandered back in time. Dick was curious to determine the attractions to both the process and product of wood firing.

I asked had he read Barry Lopez’s blazing star story about an anagama kiln firing in Oregon, USA.

He had not, and somehow my dusty copy was still in the studio book shelves.

I have a particular fondness for that story written in a muscular empathetic voice, and for a particular phrase within it.

Lopez comments that firing an anagama is less like using an instrument, more like groping in an energy field.

We discussed the role writing would play in the future of wood firing. We agreed it was likely the very longevity of the medium would be co-dependent on not only the made but what makers had to say about the made.

We discussed ancestors, respect, the crippling effect of certain post-modernist perspectives in the negation and or understanding of technique; we spoke about authenticity and specificity, we named potters we admired, we gossiped.

Most of the time Dick was picking up pots, turning them in his hand, observing foot rings, making an occasional curatorial comment. I negotiated with the blossom jar, slowly turning it on the wheel and reworking it towards a shape somewhere between cylinder and sphere.

I was reminded of Jack Troy’s comment about the hand inside the pot, which he termed the “heart hand”.

When I got to the point of construction where a suggestion of a lip rises off the shoulder of the pot, I asked for Dick’s opinion. We looked at two or three options before settling on one. It was our first collaboration.

………. ………. ……….

My friend Kim Se Wan, or Wanny, is a hard working Korean Potter. His studio is near Yeoju, about an hour and a half south east of Seoul.

Wanny rings me occasionally, usually late because of his work patterns and the time difference.

Recently he told me there are three styles of Moon Jar. His categorisation is determined by glaze.

Two are very similar, with the porcelain clay body clothed in either a shiny translucent glaze or a slightly opaque, semi matt version.

This is the surface which better brings to my mind the moon. As he speaks, I walk outside to view the very thing.

It’s in the west, behind that same forest, and I observe how differently sunlight and this opalescent moon light penetrate the same labyrinth of trunks and branches.

It’s as if moonlight is a slower light. A physicist could enlighten me, but perhaps reflected light is. It’s obviously softer but it seems more finger like. More like the moon is bathing the trees rather than feeding them.

…………. …………… ……………

Two weeks later, Dick calls.

He has been admitted to hospital.

He has had some circulation problems. I recall his comments concerning emphysema and his struggle up the studio hill.

There is concern he may have a leg amputated.

I think about the moon as a metaphor. For many things, including ceramic vases. I think about its monthly traverse, and those occasions when, after the sun sets, and before the moon rises, the sky is lightless

Dick Aitken, Lover of Ceramic Art, 1936 - 2017

Comments